There was always something different about China’s version of authoritarianism. For decades, as other regimes collapsed or curdled into dysfunctional pretend democracies, China’s held strong, even prospered.

There was always something different about China’s version of authoritarianism. For decades, as other regimes collapsed or curdled into dysfunctional pretend democracies, China’s held strong, even prospered.

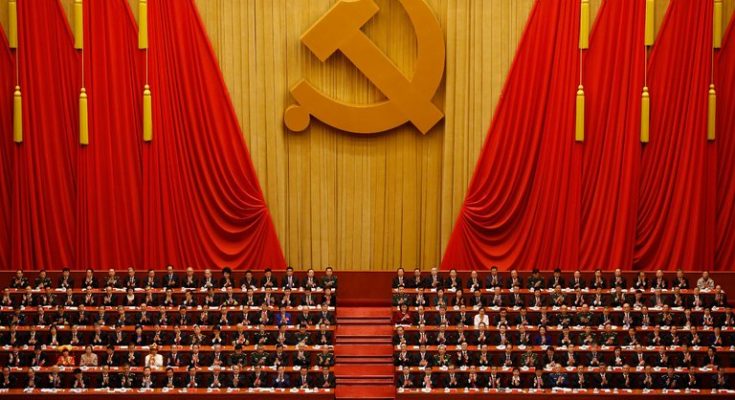

Yes, China’s Communist Party has been vigorous in suppressing dissent and crushing potential challenges. But some argue that it has survived in part by developing unusually strong institutions, bound by strict rules and norms. Two of the most important have been collective leadership — rule by consensus rather than strongman — and term limits.

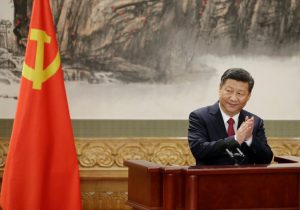

When the Communist Party announced this week that it would end presidential term limits, allowing Xi Jinping to hold office indefinitely, it shattered those norms. It may also have accelerated what many scholars believe is China’s collision course with the forces of history it has so long managed to evade.

That history suggests that Beijing’s leaders are on what former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton once called a “fool’s errand”: trying to uphold a system of government that cannot survive in the modern era. But Mr. Xi, by shifting toward a strongman style of rule, is doubling down on the idea that China is different and can refashion an authoritarianism for this age.

If he succeeds, he will not only have secured his own future and extended the future of China’s Communist Party, he may also establish a new model for authoritarianism to thrive worldwide.

The Harder Kind of Dictatorship

If Mr. Xi stays in office for life, as many now expect, that will only formalize a process he has undertaken for years: stripping power away from China’s institutions and accumulating it for himself.

It helps to mentally divide dictatorships into two categories: institutional and personalist. The first operates through committees, bureaucracies and something like consensus. The second runs through a single charismatic leader.

China, once an almost Socratic ideal of the first model, is increasingly a hybrid of both. Mr. Xi has made himself “the dominant actor in financial regulation and environmental policy” as well as economic policy, according to a paper by Barry Naughton, a China scholar at the University of California, San Diego.

Mr. Xi has also led sweeping anti-corruption campaigns that have disproportionately purged members of rival political factions, strengthening himself but undermining China’s consensus-driven approach.

This version of authoritarianism is harder to maintain, according to research by Erica Frantz, a scholar of authoritarianism at Michigan State University. “In general, personalization is not a good development,” Ms. Frantz said.

The downsides are often subtle. Domestic politics tend to be more volatile, governing more erratic and foreign policy more aggressive, studies find. But the clearest risk comes with succession.

“There’s a question I like to ask Russia specialists: ‘If Putin has a heart attack tomorrow, what happens?’” said Milan Svolik, a Yale University political scientist. “Nobody knows.”

“In China, up until now, the answer to that had been very clear,” he said. A dead leader would have left behind a set of widely agreed rules for what was to be done and there would be a political consensus on how to do it.

“This change seems to disrupt that,” Mr. Svolik said. Mr. Xi, by defying the norms of succession, has shown that any rule could be broken. “The key norm, once that’s out, it seems like everything’s an option,” Mr. Svolik said.

Factional purges risk shifting political norms from consensus to zero-sum, and sometimes life-or-death, infighting.

And Mr. Xi is undermining the institutionalism that made China’s authoritarianism unusually resilient. Collective leadership and orderly succession, both put in place after Mao Zedong’s disastrous tenure, have allowed for relatively effective and stable governing.

Ken Opalo, a Georgetown University political scientist, wrote after China’s announcement that orderly transitions were “perhaps the most important indicator of political development.” Lifelong presidencies, he said, “freeze specific groups of elites out of power. And remove incentives for those in power to be accountable and innovate.”

What Makes Authoritarian Legitimacy

In 2005, Bruce Gilley, a political scientist, wrestled with one of the most important questions for any government — is it viewed by its citizens as legitimate? — into a numerical score, determined by sophisticated measurements of how those citizens behave.

China, his study found, enjoyed higher legitimacy than many democracies and every other non-democracy besides Azerbaijan. He credited economic growth, nationalist sentiment and collective leadership.

But when Mr. Gilley revisited his metrics in 2012, he found that China’s score had plummeted.

His data showed the leading edge of a force long thought to doom China’s system. Known as “modernization theory,” it says that once citizens reach a certain level of wealth, they will demand things like public accountability, free expression and a role in government. Authoritarian states, unable to meet these demands, either transition to democracy or collapse amid unrest.

This challenge, overcome by no other modern authoritarian regime except those wealthy enough to buy off their citizens, requires new sources of legitimacy. Economic growth is slowing. Nationalism, though once effective at rallying support, is increasingly difficult to control and prone to backfiring. Citizen demands are growing.

So China is instead promoting “ideology and collective social values” that equate the government with Chinese culture, according to research by the China scholar Heike Holbig and Mr. Gilley. Patriotic songs and school textbooks have proliferated. So have mentions of “Xi Jinping Thought,” now an official ideology.

Mr. Xi’s personalization of power seems to borrow from both old-style strongmen and the new-style populists rising among the world’s democracies.

But, in this way, it is a high-risk and partial solution to China’s needs. A cult of personality can do for a few years or perhaps decades, but not more.

‘Accountability Without Democracy’

China is experimenting with a form of authoritarianism that, if successful, could close the seemingly unbridgeable gap between what its citizens demand and what it can deliver.

Authoritarian governments are, by definition, unaccountable. But some towns and small cities in China are opening limited, controlled channels of public participation. For example, a program called “Mayor’s Mailboxes” allows citizens to voice demands or complaints, and rewards officials who comply.

The program, one study found, significantly improved the quality of governing and citizens’ happiness with the state. No one would call these towns democratic. But it felt enough like democracy to satisfy some.

This sort of innovation began with local communities that expressed their will through limited but persistent dissent and protest. Lily L. Tsai, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology scholar, termed it “accountability without democracy.”

Now, some officials are adapting this once-resisted trend into deliberate practice. Their goal is not to bring about liberalization but to resist it — to “siphon off popular discontent without destabilizing the system as a whole,” the China scholars Vivienne Shue and Patricia M. Thornton write in a new book on governing in China.

Most Chinese, Beijing seems to hope, will accept authoritarian rule if it delivers at least some of the benefits promised by democracy: moderately good government, somewhat responsive officials and free speech within sharp bounds. Citizens who demand more face censorship and oppression that can be among the harshest in the world.

That new sort of system could do more than overcome China’s conflict with the forces of history. It could provide a model of authoritarianism to thrive globally, showing, Ms. Shue and Ms. Thornton write, “how non-democracies may not only survive but succeed over time.”

But Mr. Xi’s power grab, by undermining institutions and promoting all-or-nothing factionalism, risks making that sort of innovation riskier and more difficult.

When leaders consolidate power for themselves, Ms. Frantz said, “over time their ability to get a good read on the country’s political climate diminishes.”

Such complications are why Thomas Pepinsky, a Cornell University political scientist, wrote on Twitter, “I’m no China expert, but centralizing power in the hands of one leader sounds like the most typical thing that a decaying authoritarian state would do.”